Core concepts¶

The Dependency Graph¶

At the heart of Layer Linter is a graph of internal dependencies within a Python code base. This is a graph in a mathematical sense: a collection of items with relationships between them. In this case, the items are Python modules, and the relationships are imports between them.

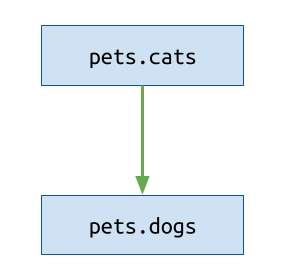

For example, a project named pets with two modules, where pets.dogs imports pets.cats, would have a graph

like this:

Note the direction of the arrow, which we’ll use throughout: the arrow points from the imported module into the importing module.

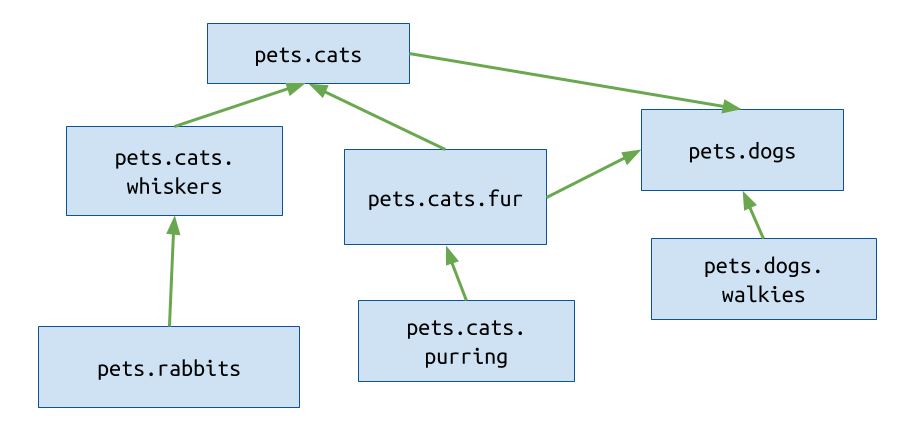

If the project was larger, it would have a more complex graph:

When you run Layer Linter, it statically analyses all of your code to produce a graph like this. (Note: these are just visual representations of the underlying data structure; Layer Linter has no visual output.)

Layers¶

Layers are a concept used in software architecture. They describe an application organized into distinct sections, or layers.

In such an architecture, lower layers should be ignorant of higher ones. This means that code in a higher layer can use utilities provided in a lower layer, but not the other way around. In other words, there is a dependency flow from low to high.

Layers in Python

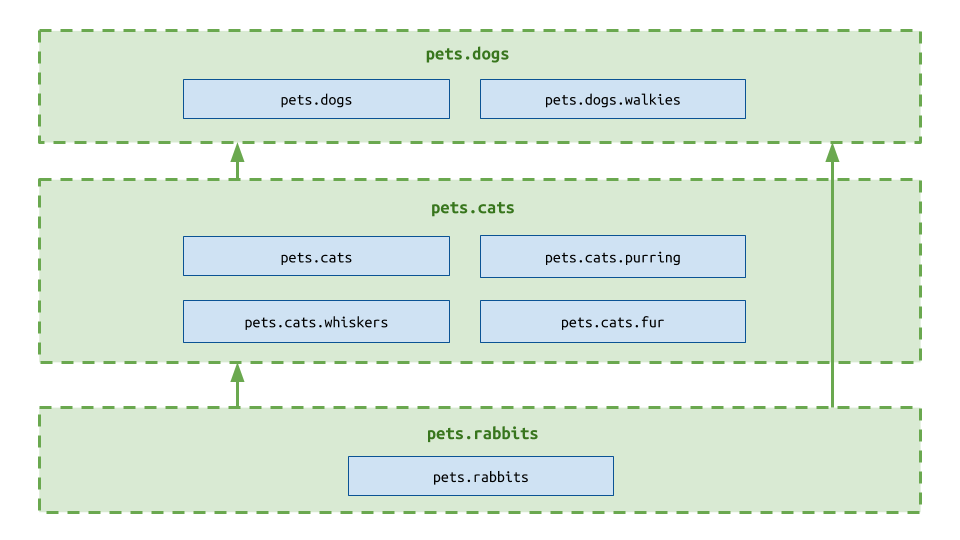

In Python, you can think of a layer as a single .py file, or a package containing

multiple .py files. This layer is grouped with other layers, all sharing a common parent package:

in other words, a group of layers will all be in the same directory, at the same level.

Layer Linter calls this common parent a container.

Within a single group of layers, any file within a higher up layer may import from any file lower down, but not the other way around - even indirectly.

The above example shows a single group consisting of three layers. Their container is the top level package, pets.

According to the constraints imposed by layers, pets.cats.purring may import pets.rabbits but not

pets.dogs.walkies. pets.dogs.walkies may import any other module, as it is in the highest layer.

(For further reading on Layers, see the Wikipedia page on Multitier Architecture).

Contracts¶

Contracts are how you describe your architecture to Layer Linter. You write them in a layers.yml file. Each

Contract contains two lists, layers and containers.

layerstakes the form of an ordered list with the name of each layer module, relative to its parent package. The order is from high level layer to low level layer.containerslists the parent modules of the layers, as absolute names that you could import, such asmypackage.foo. If you have only one set of layers, there will be only one container: the top level package. However, you could choose to have a repeating pattern of layers across multiple subpackages; in which case, you would include each of those subpackages in the containers list.

You can have as many of these contracts as you like, and you give each one a name.

Example: single container contract

The three-layered structure described earlier can be described by the following contract. Note that the layers have names relative to the single, containing package.

Three-tier contract:

containers:

- pets

layers:

- dogs

- cats

- rabbits

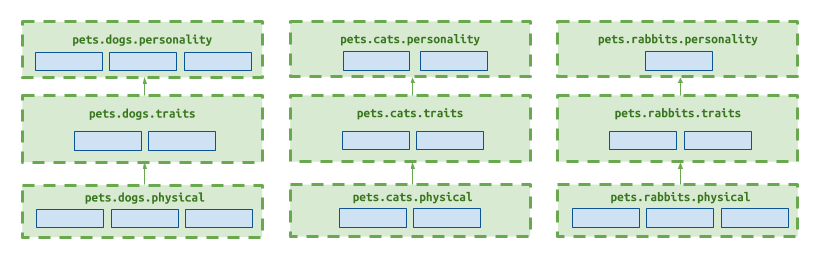

Example: multiple package contract

A more complex architecture might involve the same layers repeated across multiple containers, like this:

In this case, rather than have three contracts, one for each container, you may list all the containers in a single contract. The order of the containers is not important.

Modular contract:

containers:

- pets.dogs

- pets.cats

- pets.rabbits

layers:

- personality

- traits

- physical

Whitelisting paths¶

Sometimes, you may wish to tolerate certain dependencies that do not adhere to your contract. To do this, include them as whitelisted paths in your contract.

Let’s say you have a project that has a utils module that introduces an illegal dependency between two

of your layers. The report might look something like this:

----------------

Broken contracts

----------------

My layer contract

-----------------

1. pets.cats.whiskers imports pets.dogs.walkies:

pets.cats.whiskers <-

pets.utils <-

pets.dogs.walkies

To suppress this error, you may add one component of the path to the contract like so:

Three-tier contract:

containers:

- pets

layers:

- dogs

- cats

- rabbits

whitelisted_paths:

- pets.cats.whiskers <- pets.utils

Running the linter again will show the contract passing.

There are a few use cases:

- Your project does not completely adhere to the contract, but you want to prevent it getting worse. You can whitelist any known issues, and gradually fix them.

- You have an exceptional circumstance in your project that you are comfortable with, and don’t wish to fix.

- You want to understand how many dependencies you would need to fix before a project conforms to a particular architecture. Because Layer Linter only shows the most direct dependency violation, whitelisting paths can reveal less direct ones.